Removing Bees from a Chimney

by Paul Hooper

Having removed a well established hive from the wall cavity of a weatherboard farmhouse, I was asked if I could then remove another colony from a blocked-in chimney in the same house. The hive had been active for more than 20 years and reached up to the very top of the chimney, where it was directly exposed to the elements. The depth of the comb could not be determined because the associated fireplace had been securely closed and walled in.

The home owner was very keen to ensure the bees were not killed and that leakage of honey from any meltdown of unventilated comb in the hot weather was avoided.

Intrigued by the challenge, I decided to use an “escape method” along the lines of one described in Chapman-Taylor and Davey’s 1981 book “Beekeeping for Fun”. Essentially, the plan was to remove the bees, then to use those same bees to rob-out the honey from the old hive, and finally to fully seal the chimney and let the wax moth destroy the comb. The intended time-scale was six weeks. Removal of the bees was achieved by sealing all but one entrance to the hive, and placing a one-way escape on that remaining entrance. A single box hive was placed such that its entrance was adjacent to the escape. During all this activity the bees were very busy, going about their normal business apparently oblivious to the changes taking place in their environment. At no stage during the entire seven week operation did any of the bees exhibit any aggression – until the box hive was finally closed up and removed from its perch on the chimney.   Â

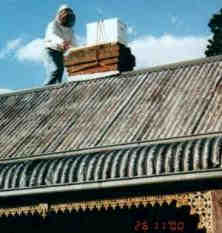

Removal of the bees was achieved by sealing all but one entrance to the hive, and placing a one-way escape on that remaining entrance. A single box hive was placed such that its entrance was adjacent to the escape. During all this activity the bees were very busy, going about their normal business apparently oblivious to the changes taking place in their environment. At no stage during the entire seven week operation did any of the bees exhibit any aggression – until the box hive was finally closed up and removed from its perch on the chimney.   Â

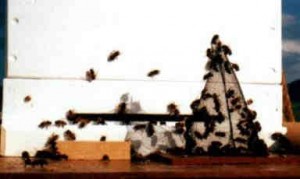

The following sequence of photos shows: the chimney before starting, gaps sealed with foam strips, the sealing board in place (with its one circular entrance), and the escape. The escape was a cone made of aluminium flywire, about 4 inches (100mm) diameter at the base and open 3/8 inch (9mm) diameter at the top. The ends of the wires around the top hole were arranged to make re-entry as difficult as possible.

Onc

Onc e the cone escape assembly was screwed over the entrance the box hive was placed in position and securely tied down with rope to prevent dislodgement by strong winds. This hive contained a small swarm hived a week before on foundation. The swarm had partially drawn two frames of foundation, stored a little nectar and the queen had started laying. Chapman-Taylor and Davey suggest the collecting box be “baited with one frame of brood including eggs and one of stores, both covered with nurse bees”, the collected bees then raising a new queen. I am sure that the latter would work but, rather than disturb another hive, I preferred to use the new small swarm.

e the cone escape assembly was screwed over the entrance the box hive was placed in position and securely tied down with rope to prevent dislodgement by strong winds. This hive contained a small swarm hived a week before on foundation. The swarm had partially drawn two frames of foundation, stored a little nectar and the queen had started laying. Chapman-Taylor and Davey suggest the collecting box be “baited with one frame of brood including eggs and one of stores, both covered with nurse bees”, the collected bees then raising a new queen. I am sure that the latter would work but, rather than disturb another hive, I preferred to use the new small swarm.

In the two photos above, taken four days after installation, the bees can be seen emerging from the cone and trying to re-enter the cone. During a total of about one hour’s observation only two bees were seen to successfully re-enter the cone, meanwhile hundreds of bees had exited. The desired outcome was that the foraging bees would leave the chimney hive and on their return, unable to re-enter the chimney, drift into the adjacent box hive. Subsequently, the younger bees would also leave the chimney and end up in the box hive. The chimney queen would soon slow down and discontinue laying as the loss of foragers became evident. Nurse bees would continue attending the brood, using stored honey and pollen, until all brood was hatched and eventually left the chimney. The fate of the queen was uncertain; she would either emerge eventually or die unattended.

In the two photos above, taken four days after installation, the bees can be seen emerging from the cone and trying to re-enter the cone. During a total of about one hour’s observation only two bees were seen to successfully re-enter the cone, meanwhile hundreds of bees had exited. The desired outcome was that the foraging bees would leave the chimney hive and on their return, unable to re-enter the chimney, drift into the adjacent box hive. Subsequently, the younger bees would also leave the chimney and end up in the box hive. The chimney queen would soon slow down and discontinue laying as the loss of foragers became evident. Nurse bees would continue attending the brood, using stored honey and pollen, until all brood was hatched and eventually left the chimney. The fate of the queen was uncertain; she would either emerge eventually or die unattended.

Inspection of the box hive after seven days revealed that it was rapidly filling with bees and comb was being drawn on all frames. A second box was added. A further inspection another week later revealed comb drawing in the top box and a much reduced activity in the chimney. The initial plan was to remove the cone escape five weeks after it had been put in so that the bees, now established in the box hive, would enter the chimney and rob the old hive of any remaining honey. Circumstances delayed the escape removal until six weeks from the starting date. Having done this, the chimney entrance was left open for a further week before the box hive and all other paraphernalia was removed.

Nothing was easy working on a tin roof, sometimes in very hot conditions, but one man getting a reasonably full two-box hive off a chimney, across a sloping roof and down to the ground was fraught with some danger. The hive was lifted off the chimney, carried across the roof and lowered to the ground on a rope. In the event, despite the Emlock being quite tight, the hive sections did slip a little, but not enough to let bees out. However, a small indiscretion with the entrance closer did let about 20 angry bees out.

Once the box hive was removed the comb in the chimney was examined and found to be completely empty, apart from a little pollen. All brood had hatched, all honey removed and there was no sign of the queen or any other bees. Wax moth had just started to work on the comb. The comb was found to extend only a metre down the chimney as the chimney had been blocked off just below that level, either by man or bird, long ago. Consequently, the comb was not left to the moth but was removed and the wax recovered.

To complete the job the loose bricks atop the chimney were mortared in together with a sheet of Hardieplank covering the opening to block all holes and hopefully prevent any re-colonisation. The box hive was taken some 20 kilometres away and has prospered.

Observations:

I believe the effort would be futile if all exits from the hive could not be blocked. I was lucky this time, but all other hives I have observed in dwellings have had access to a number of discreet exits.

Other styles of escape were considered before deciding on the cone. Porter escapes offered the security that bees certainly would not be able to return. But there were a lot of drones in the chimney and, as the system had to be left unsupervised for up to a month because of its remote location, even multiple Porter escapes would possibly be blocked by stuck drones. So, even though there was very little published about the efficacy of the cone escape, the cone was used.

Would I do it again? Only as a very special favour.

This article was published first in the February 2001 issue of the newsletter of the Beekeepers Association of the ACT.

Like us on Facebook

Like us on Facebook